As I wrote in May 2017, the number of publicly listed companies in the U.S. has fallen steadily since 1997. More companies have delisted, in fact, than gone public in every year of the past 20 years except one, 2013.

Put another way, the pool is getting smaller even while the population and economy are expanding.

The U.S. Has 5,000 Fewer Listed Companies Than It Should

In 1976, there were about 23 listed companies per 1 million U.S. citizens. Today, it’s closer to 11 per million.

That’s according to a new National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) report by respected financial economist René Stulz, who adds that the U.S. has roughly 5,000 fewer companies listed on exchanges than you would normally expect, given the country’s size, population, economic and financial development and respect for shareholder rights.

Are we seeing the same phenomenon in other countries, developed or otherwise?

“There are other countries that have lost listings since 1997, but few have experienced a greater percentage decrease in listings,” Stulz writes. “Further, the U.S. is in bad company in terms of the percentage decrease in listings—just ahead of Venezuela.”

Given that Venezuela’s economy is in freefall, with inflation forecast to hit 1 million percent this year, I would call it bad company indeed.

So why is this happening?

A Record $2.5 Trillion in M&A Activity

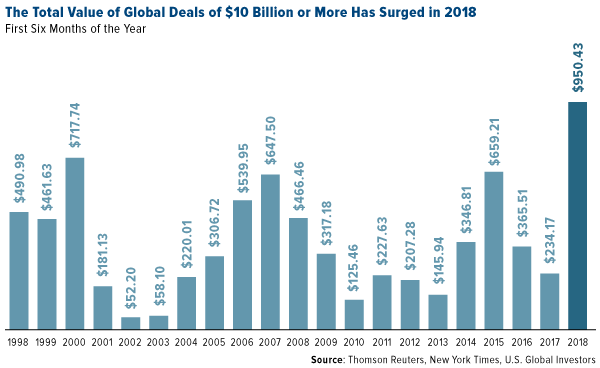

One of the main causes of fewer listings is the explosion in mergers and acquisitions (M&As). When one company acquires another, or when two companies merge, that lowers the number of traded stocks—assuming they were available to be traded to begin with. So far this year, worldwide M&A activity has been very robust, with a record $2.5 trillion in deals announced in the first six months alone. That puts 2018 on track to surpass $5 trillion, which would be the most ever recorded.

What also makes 2018 different from past years is the high number of mega-deals that exceed $10 billion. Together, these deals total $950 billion, more than in any past first-six-month period.

Among the biggest deals is AT&T’s takeover of Time Warner, valued at $85 billion. Coincidentally, that’s about $80 billion less than the deal that merged Time Warner and America Online (AOL) back in 2000, still the largest in history.

There’s nothing wrong with M&As, of course. The problem arises when there aren’t enough initial public offerings (IPOs) to replenish the pool and give investors early access to new firms.

At the most basic level, fewer stocks means fewer options. It becomes more difficult to build a diversified portfolio when you don’t have a diversity of stocks to choose from.

Consider how many companies Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has acquired over the years. It owns recognizable brands like Duracell, Dairy Queen, GEICO, Fruit of the Loom and more, not to mention is the majority owner of a number of other companies. There’s even talk that Buffett might buy a domestic airline outright, possibly Southwest.

But at more than $311,000 a share right now, Berkshire’s A stock is out of most Main Street investors’ price range. How long until they’re priced out of participating in the entire market?

What’s more, profits are being divided among fewer winners. This is contributing to inflated valuations and market frothiness. In many ways, Apple can thank its $1 trillion market cap largely on the fact that there’s less competition now among equities—specifically tech equities. Uber, Airbnb, Pinterest, Coinbase, and many other huge tech unicorns have delayed or put off getting listed altogether.

Tougher Regulations Have Contributed to Private Equity Boom

So why would a company like Uber or Airbnb choose not to seek public funding? We can point to two related causes: stricter regulations on publicly traded firms, and the boom in private equity.

The most reported among these regulations is the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. More commonly known as SOX, the law was passed and signed in 2002 in response to major accounting scandals that brought down WorldCom and Enron.

In May 2017, I named SOX one of the five costliest financial regulations of the past 20 years. Its notorious Section 404, which requires external auditors to report on the adequacy of a firm’s internal controls, disproportionately hurts smaller companies, costing them six times as much in accounting fees in relation to larger firms, according to estimates by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Because of these added costs, many smaller companies and startups are opting not to raise funds from public capital markets—or at least to delay it.

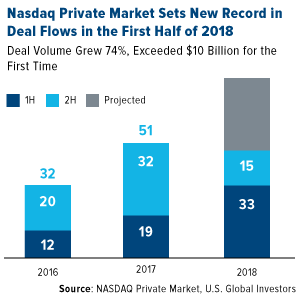

In the meantime, firms are finding it easier to get adequate private financing—which Main Street investors don’t have access to. According to Reuters, the global private equity industry raised $453 billion from investors in 2017, a new record. And last week, Nasdaq Private Market (NPM), which helps companies facilitate shareholder liquidity, announced it conducted a record 33 company sponsored liquidity programs in the first half of 2018. Deal volume grew 74 percent compared to the same period last year and exceeded $10 billion for the first time.

You can see now why some companies like Uber are staying private for longer. Some prefer not to have added costs associated with compliance. Others might not want to answer to a board or share financial details publicly.

These are among the things Elon Musk apparently wants to avoid by taking Tesla private. He’s become more combative with analysts and shareholders, especially short sellers, going so far as to tell listeners during a May conference call to “sell [Tesla] stock and don’t buy it” if they’re concerned about volatility.

Before SOX, the average age of a company at the time of its IPO was 3.1 years. Today, it’s more like 13.3 years, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

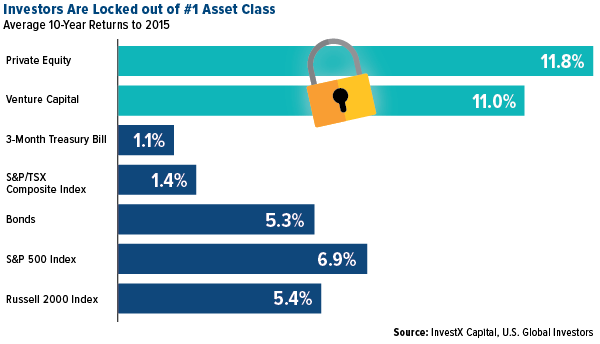

This hurts Main Street investors. Because they’re generally not able to invest in private equity, they lack access to companies when they might be expanding at their fastest pace.

Check out the chart below. In the 10-year period through 2015, private equity and venture capital averaged 11 percent or more annually. They far outperformed stocks and bonds, sometimes by more than double.

Here's what investors can do… Full story at U.S. Global Investors